The Hidden Stress of China's Only Children

- Date:

- Views:68

- Source:The Silk Road Echo

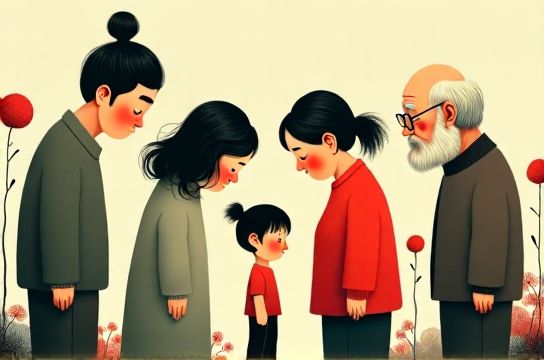

In the shadow of China’s once-in-a-generation One-Child Policy, a quiet emotional crisis has been simmering. For decades, over 180 million only children grew up bearing the weight of sky-high expectations, family survival hopes, and crushing loneliness. We call them the ‘Little Emperors’—but behind the privilege lies a deep well of hidden stress.

The Emotional Burden of Being the Only One

Born between the 1980s and early 2010s, China’s only children were raised with one mission: succeed. With all parental dreams funneled into a single child, academic pressure starts as early as preschool. A 2022 study by Peking University found that 68% of only children report chronic anxiety, compared to 43% among those with siblings.

But it’s not just about grades. These young adults now face the ‘4-2-1 problem’—supporting two parents and four grandparents, often alone. As China ages rapidly, this burden is becoming unsustainable.

Numbers Don’t Lie: The Pressure in Data

Let’s break it down with real stats:

| Metric | Only Children | With Siblings |

|---|---|---|

| Reported Anxiety (Age 18–30) | 68% | 43% |

| Monthly Financial Support to Parents | ¥3,200 | ¥1,500 |

| Feelings of Loneliness | 57% | 31% |

| Desire for Mental Health Counseling | 49% | 28% |

Source: National Health Commission & Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (2023)

The Loneliness Epidemic

No siblings mean no built-in emotional backup. When parents fall ill or pass away, many only children describe feeling like ‘the last pillar standing.’ In cities like Beijing and Shanghai, over 40% of only children live more than 500km from their parents, making caregiving a logistical nightmare.

Social media reflects this pain. On Douban, a popular forum, threads titled ‘I’m an only child and I’m terrified of my parents dying’ have tens of thousands of views. One user wrote: ‘If something happens to them, I’ll have no one who truly knows my childhood.’

Breaking the Silence

Thankfully, change is coming. Mental health awareness is rising, especially among Gen Z. More young adults are seeking therapy, joining support groups, and openly discussing emotional strain. Universities now offer counseling tailored to only children, recognizing their unique pressures.

And while the One-Child Policy officially ended in 2016, its psychological legacy lingers. The government has begun funding elder-care programs to ease the 4-2-1 burden, but emotional support systems remain underdeveloped.

What Can Be Done?

- Normalize therapy: Break the stigma around mental health.

- Expand community care: Build networks so no one faces aging parents alone.

- Reframe success: Let kids be kids, not family saviors.

China’s only children weren’t just policy products—they’re human stories shaped by love, duty, and silent struggle. It’s time we listen.