How Chinese Internet Users Subvert Censorship with Memes and Wordplay

- Date:

- Views:82

- Source:The Silk Road Echo

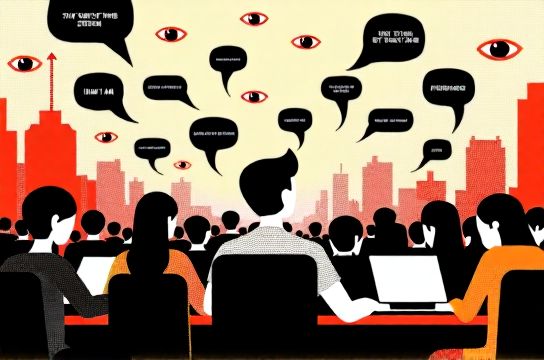

In the world's most monitored digital landscape, Chinese netizens have turned censorship into a creative challenge. With over 1.05 billion internet users navigating strict online controls, a vibrant culture of linguistic rebellion has emerged—where memes, puns, and wordplay become tools of subtle resistance.

Rather than direct confrontation, users rely on zhongguo tifa (China-specific expression methods)—a mix of satire, homophones, and absurd imagery—to bypass automated filters. Take the word “harmony” (hexie 和谐), officially promoted as social stability, but repurposed online to mean censorship because it sounds like “he xie” (to be removed). When users say “Let’s go eat harmonious food,” they’re not dining—they’re dodging detection.

Another classic? The duck known as “Grass-Mud Horse” (草泥马). Sounds innocent? In Mandarin, it’s a homophone for a vulgar insult. This meme exploded in 2009 when Baidu Encyclopedia briefly banned politically sensitive terms. Netizens responded by flooding the web with images of alpaca-like creatures labeled “Grass-Mud Horse,” creating an absurdist fable set in the “Mahler Gobi Desert” (a pun on another curse phrase). It wasn’t just a joke—it was a viral act of defiance.

Platforms like Weibo and Douban use AI-driven keyword filters, but users stay one step ahead. Here’s how common tactics stack up:

| Tactic | Example | Purpose | Success Rate* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Homophones | “River crab” (河蟹) = “harmonize” (和谐) | Evade keyword scans | High |

| Emoji substitution | 🗣️➡️🤐 (speech to silence) | Visual critique of suppression | Medium |

| Misspellings | “Zhongguo” → “Z-guo” | Bypass text filters | Medium-High |

| Image macros | Panda wearing blindfold | Symbolic protest | High |

*Based on user reports and digital rights research (2023).

The game evolves daily. When “democracy” gets filtered, users write “minzhu” with animal characters—like “rabbit” (tuzi) representing “grassroots.” During major political events, censored hashtags reappear as doodles or song lyrics. Even numbers get repurposed: “54” stands for “Wusi” (May Fourth), a nod to historical dissent.

This isn’t just humor—it’s digital survival. As one WeChat user joked, “If censorship is the firewall, then memes are the backdoor.” And while authorities occasionally crack down (the Grass-Mud Horse was eventually banned), the creativity persists. After all, in a space where words are weapons, laughter might be the sharpest tool.